Currencies, like people, have personalities. They live, stumble, rise, and sometimes collapse. They boast, envy, cry, and pretend to be stronger than they really are. In West Africa, four characters dominate the monetary stage: the Ghanaian Cedi, the Nigerian Naira, the CFA Franc, and the elusive Eco — forever promised, forever unborn. Together, they tell the story of a region still searching for stability, dignity, and unity.

The Rise and Fall of Brothers

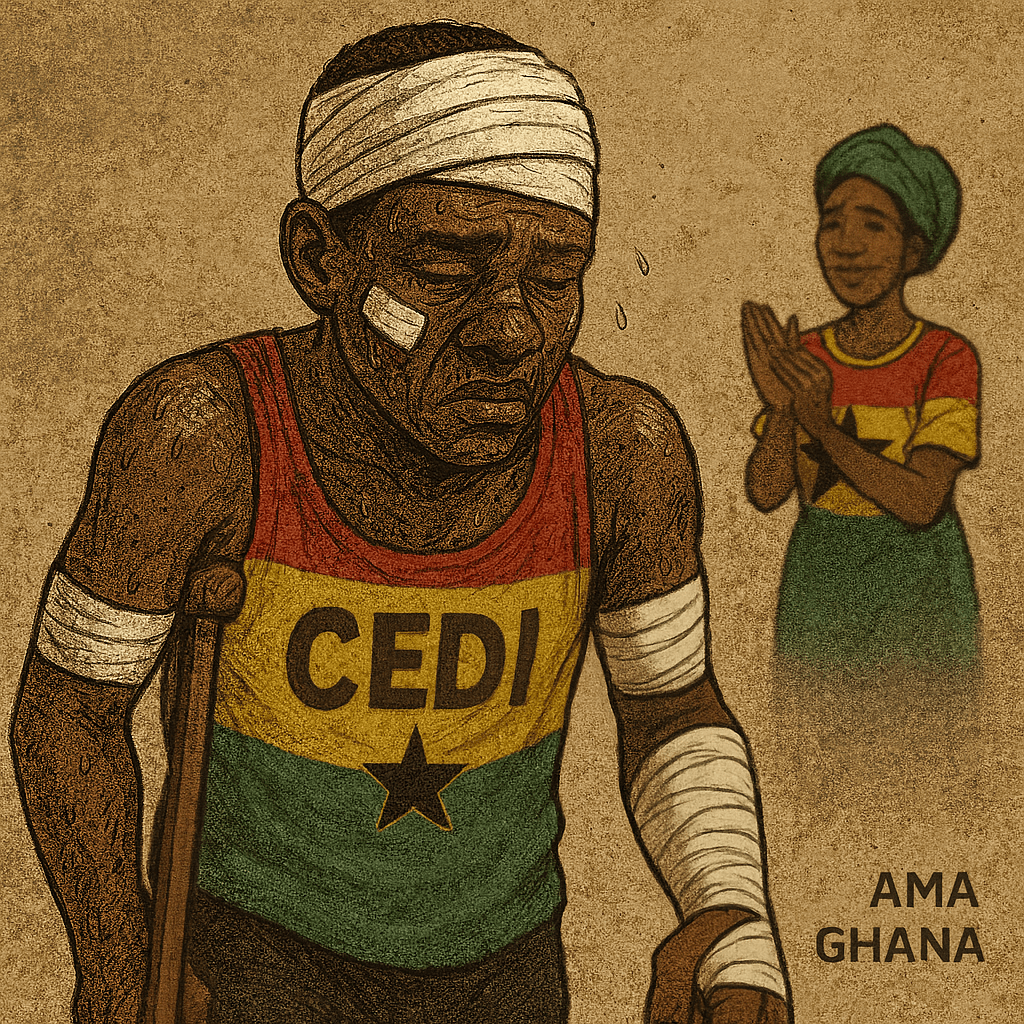

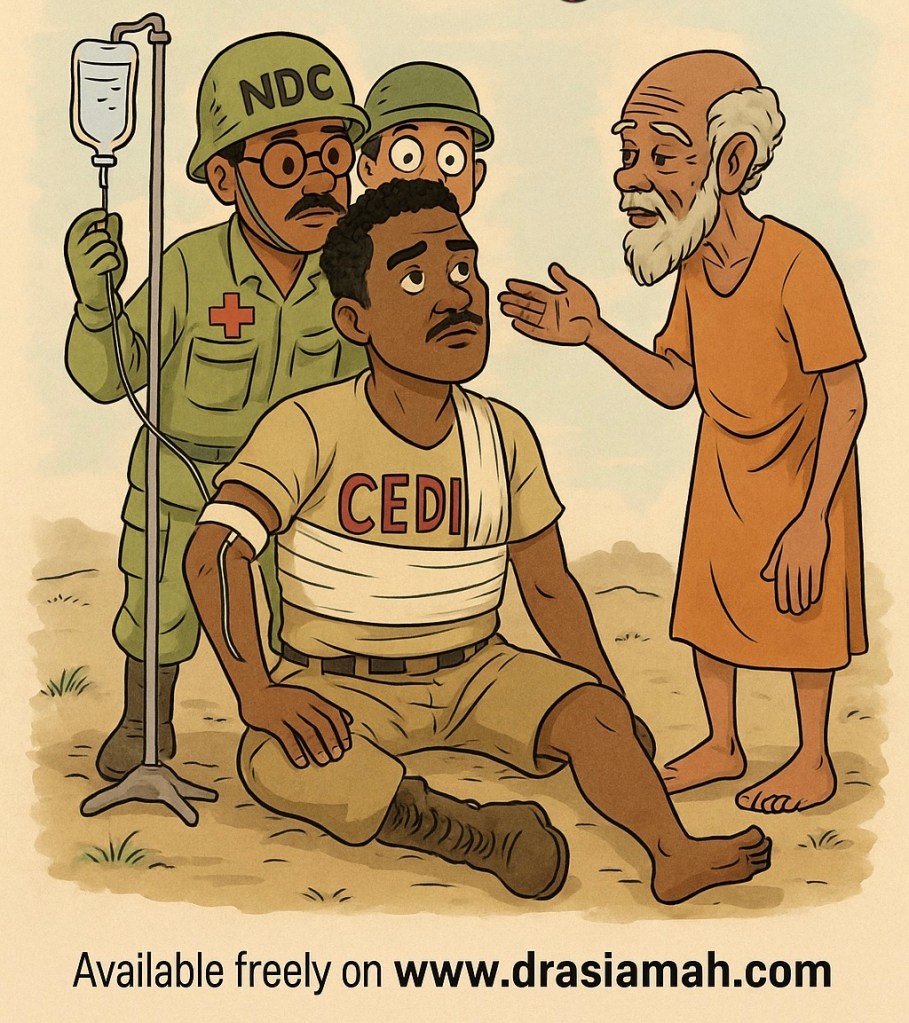

The Cedi was born in 1965, young and proud, replacing the colonial Ghanaian pound. At independence, his father Kwame Nkrumah dressed him in fine linen and sent him to walk shoulder-to-shoulder with the dollar and the pound. He was called the “prince of West Africa,” backed by cocoa, gold, and a vision of industrialization. But the fall of Nkrumah, followed by years of coups, devaluations, and IMF experiments, clipped his wings. By the 1980s, Cedi was begging in the corridors of Washington, disciplined into liberalization, his dignity bartered away at the black market.

Naira, on the other hand, was once a king. In the 1970s and early 1980s, he strode across the continent with oil wealth swelling his pockets. Nigerians traveled freely with strong Naira, shopping in London as if Oxford Street were Lagos Island. Ghana, battered by droughts and debt, looked at Naira with envy. But oil dependence is a dangerous addiction. As oil prices crashed, corruption spread, and mismanagement deepened, Naira’s muscles shrank. Inflation weakened him, parallel markets mocked him, and he now hides behind multiple exchange rates – a giant reduced to confusion.

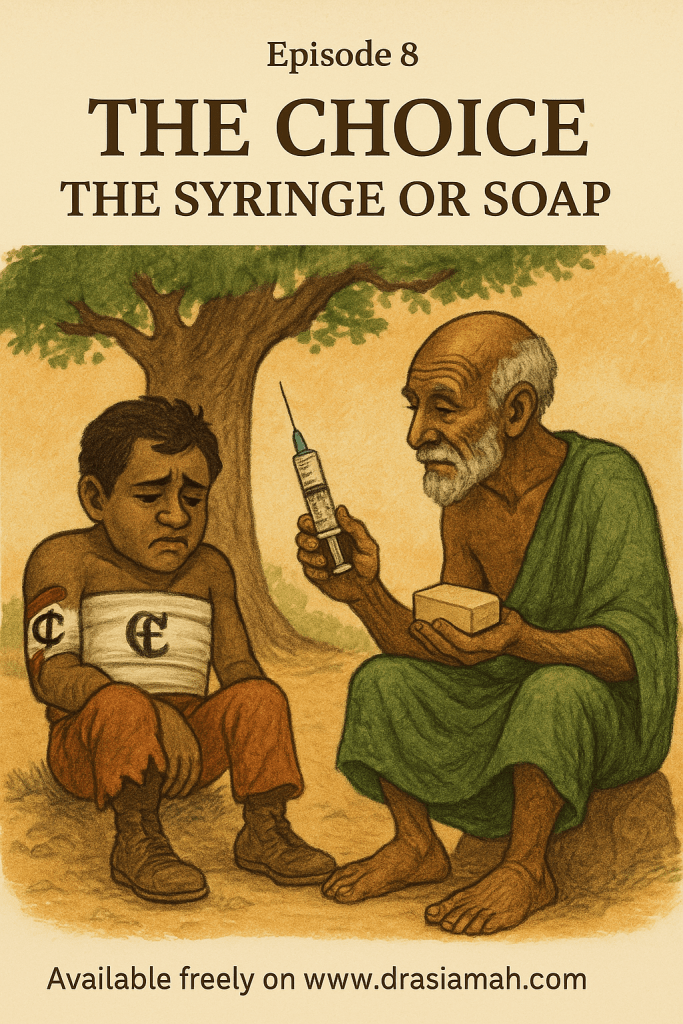

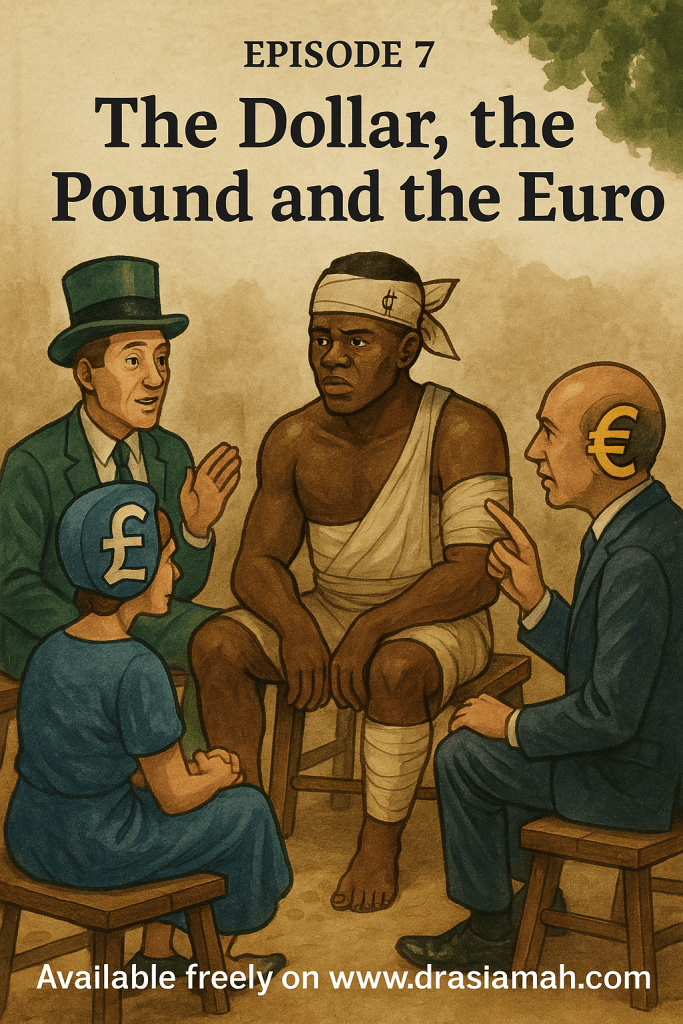

Then there is the CFA Franc, that peculiar cousin. Created in 1945 by France, the CFA has always been suspiciously neat and orderly. Pegged to the French franc, and later to the Euro, the CFA prides himself on stability. While Cedi and Naira stumble in inflation, CFA strolls in calm, admired by international investors for his predictability. But this neatness is an illusion of independence. CFA cannot decide his own fate; his policies are dictated in Paris. He is the disciplined child, yes, but only because he is still tethered to his colonial parent. The proverb says: “The sheep tied to a post does not get lost, but neither does it graze freely.” That is CFA’s curse – stability at the cost of sovereignty.

The Family Gathering

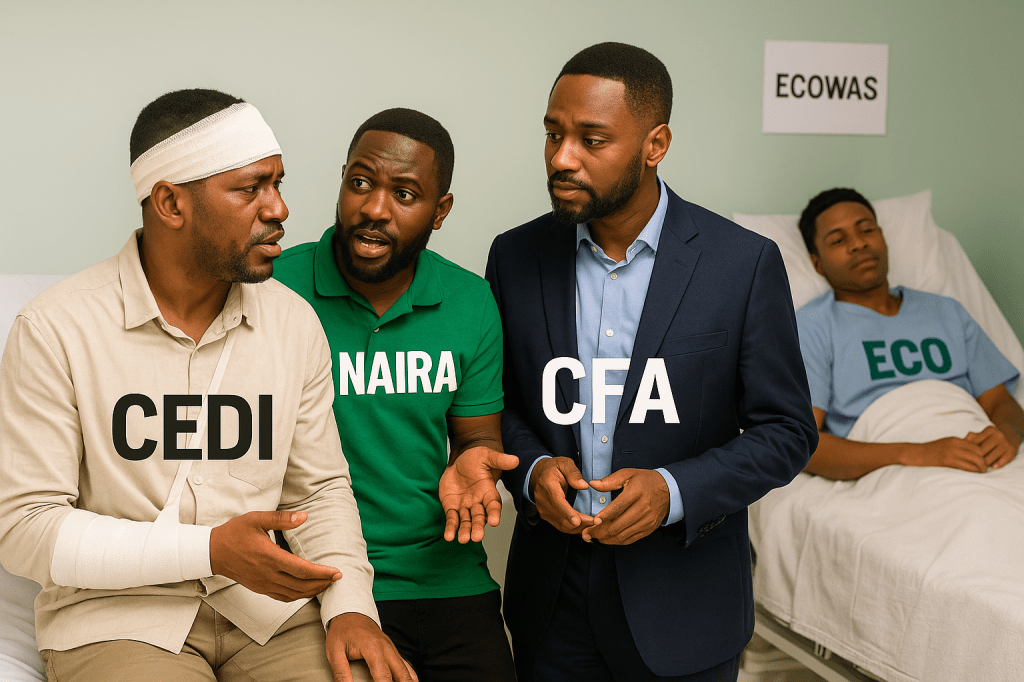

Imagine them sitting together under a baobab tree.

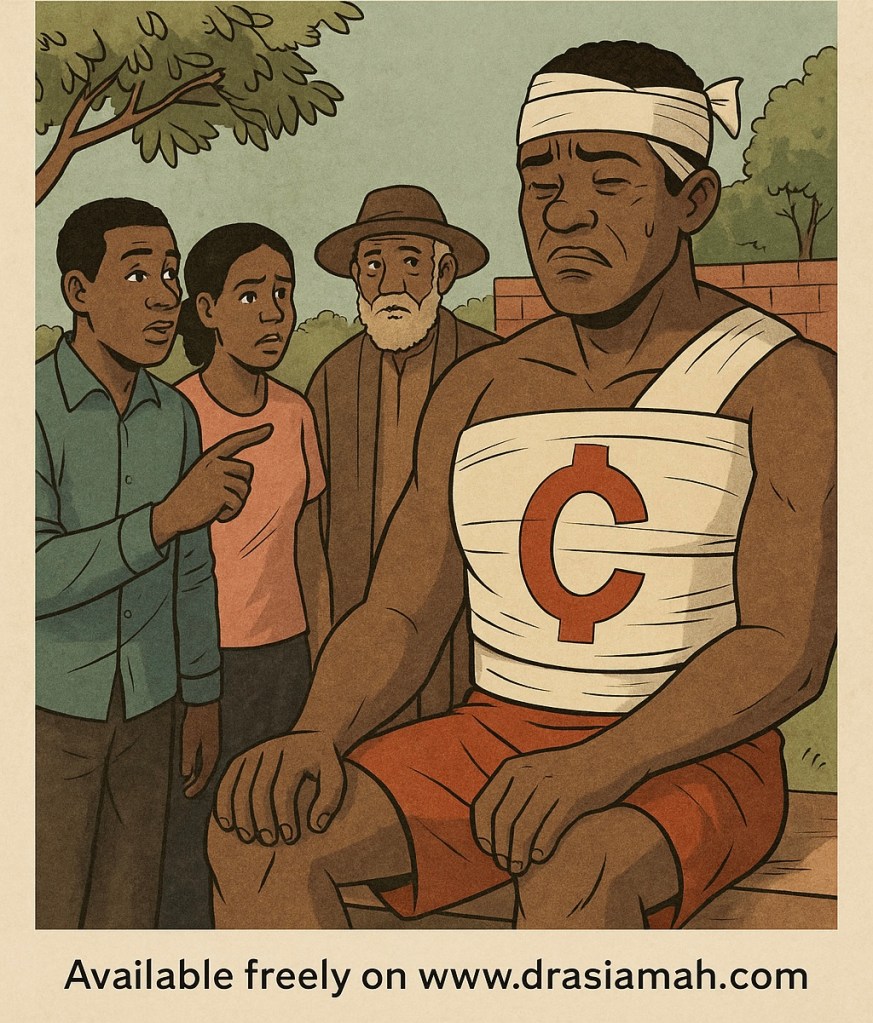

- Cedi sits with patched clothes, tired but still proud. He has survived IMF clinics, market beatings, and political abuse, yet he keeps limping forward.

- Naira arrives late, sweating, carrying oil barrels on his back. He is loud but defensive, muttering that he is still “the giant of Africa,” even as his shoes are torn.

- CFA enters next, dressed in a French suit, polished and perfumed, looking at the others with condescension. He boasts: “At least I don’t fall. At least I don’t beg.”

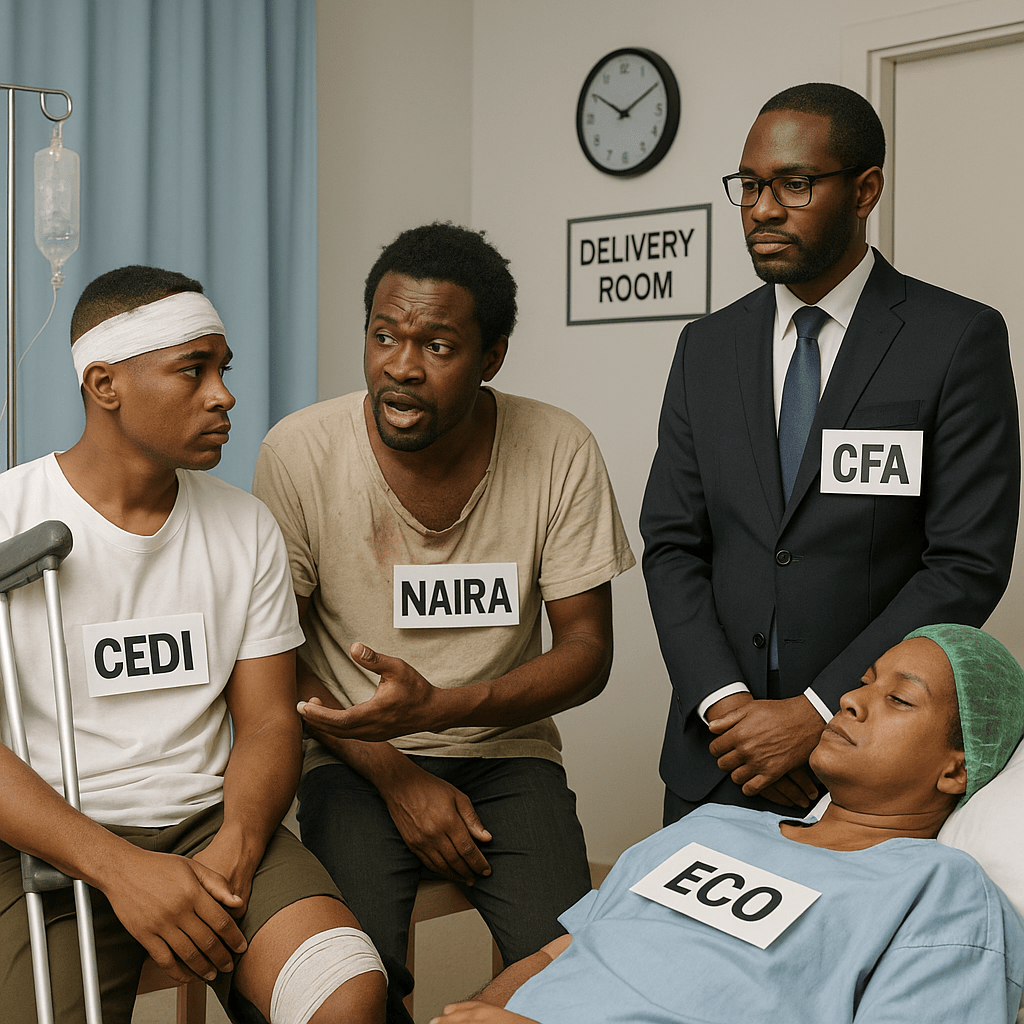

- And then there is Eco — the forever unborn child. Everyone talks about him, but nobody has seen him. Some say he is beautiful, others say he is a mirage. For decades, he has been “coming soon,” but the midwives of ECOWAS have never managed to deliver him.

The conversation begins.

Naira (to Cedi): “Ah, my brother, you are weak these days. The dollar knocks you flat every week.”

Cedi (sighing): “Yes, but even in my weakness, you still envy me. At least I am not broken into ten exchange rates, hiding from myself.”

CFA (smirking): “Both of you are children playing with fire. Look at me — stable, respected, reliable. Investors trust me, my people travel easily. I am the model of discipline.”

Cedi (laughing): “Discipline? Or dependence? You wear Paris’s shoes, eat Paris’s bread, and even when you sneeze, you must ask France for tissue. Stability without sovereignty is slavery in a suit.”

Naira (clapping): “Tell him, Cedi! He brags about his tie, but he cannot loosen it without permission.”

At this point, a faint cry is heard in the distance. It is Eco, unborn but restless, speaking from the womb of ECOWAS communiqués:

Eco (muffled): “Peace, brothers! Stop fighting. I am coming to unite you. With me, there will be no CFA, no Cedi, no Naira — just one strong West African voice.”

The brothers burst into laughter.

Cedi: “Coming? You have been ‘coming’ since the 1980s. Our fathers grew old waiting for you. Our children may die waiting too.”

Naira: “Yes, every ECOWAS summit, they say, ‘Eco is near!’ But when the meeting ends, they forget you. You are like the rainbow — beautiful but always vanishing.”

CFA (with disdain): “Even if you are born, you will still need my French doctor to cut your umbilical cord. Without Paris, you will be stillborn.”

The laughter dies down. The truth hangs in the air: Eco is a mirage, a promise without delivery, a unity that remains forever postponed.

The Mirage of Eco

The Eco dream is not new. Since 1983, ECOWAS has announced plans for a single currency. Deadlines were set: 2000, 2005, 2010, 2020… each postponed. Leaders meet, sign communiqués, and issue photos, but the implementation remains elusive. Why? Because the fundamentals are weak. Inflation, fiscal deficits, and exchange rate policies differ widely across the region. Nigeria, with its size, demands dominance; smaller economies fear being swallowed. Francophone states remain tied to France through the CFA. Unity is preached, but sovereignty is hoarded.

The Eco, therefore, has become a political slogan, not an economic reality. It is the mirage on the horizon — shimmering, enticing, but never reached.

The Political Economy of Envy

Yet beneath the failures lies an important lesson. Even in his weakness, the Cedi remains envied by Naira, because Ghana’s smaller economy still manages occasional stability that Nigeria, with all its oil, cannot achieve. CFA, though stable, secretly envies Cedi and Naira, for at least they are free to stumble on their own terms. And Eco, unborn, envies them all, because at least they exist.

This circle of envy reflects West Africa’s deeper problem: we measure ourselves against one another, instead of reimagining ourselves together. Naira dreams of being dollar, Cedi dreams of being euro, CFA dreams of being Swiss franc, Eco dreams of being born. Meanwhile, ordinary Africans just dream of money that holds value long enough to buy bread tomorrow at the same price as today.

Conclusion: The Baobab Lesson

The gathering ends under the baobab. Cedi walks away limping, Naira staggers with his oil barrels, CFA straightens his French suit, and Eco disappears back into the womb of ECOWAS communiqués.

The proverb says: “When brothers fight over inheritance, strangers inherit the land.” West Africa’s currencies fight over envy, dependency, and procrastination, while the dollar, euro, and yuan quietly dominate their markets.

The lesson is clear: unless West Africa learns to speak with one monetary voice, the Eco will remain unborn, the Cedi will keep limping, the Naira will keep groaning, and the CFA will keep smiling in borrowed shoes.

And maybe one day, when Eco finally arrives — if he ever does — he will look at his older brothers and ask: “Why did you wait so long to grow up?”